Watershed coordinators’ hands-on work improves NE Iowa streams

By Dan Looker

The Turkey River winds and ripples past limestone bluffs in Northeast Iowa and is a favorite of paddlers and anglers. But where the river starts, at a

gently sloping corn field in Howard County, it looks more like an easily jumped ditch.

Hunter Slifka, a watershed coordinator who works out of the Howard Soil & Water Conservation District in Cresco, compares this spot to the Mississippi headwaters at Lake Itasca, Minnesota, where scores of tourists step across the Mighty Mississippi’s outlet every summer. Here, near Cresco, motorists zip past a green sign marking “West Branch Turkey River.”

Slifka stops his truck by the sign and climbs down the grassy bank of a clear stream with rocks on the bottom. Nearby, water from a drainage tile gurgles into it. On dry summer days, that tile is the main source of the river.

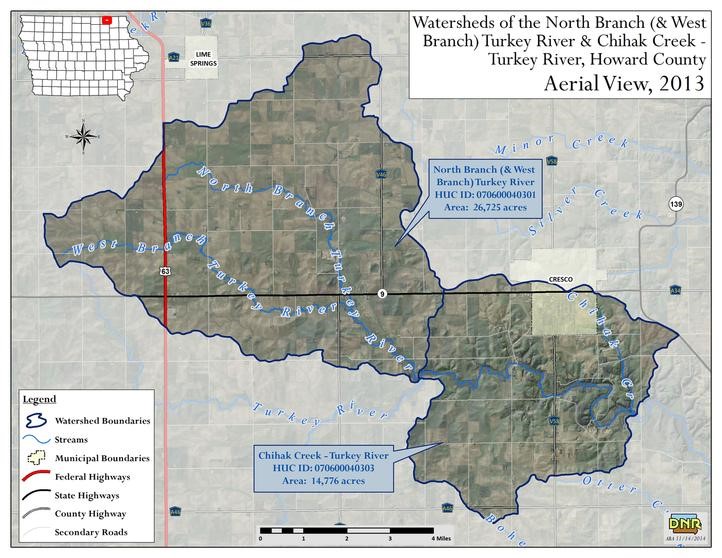

In 2015, this is where Slifka and his mentor and fellow watershed coordinator, Neil Shaffer, began an odyssey of discovery that’s leading to the transformation of a landscape. Over that summer, they walked nearly 50 miles of the North and West branches of the Turkey River. Stopping every 500 feet, they used a hand-held device to record stream features, such as water clarity and bank stability. They finished four miles a day. In 2018, they walked another 20 miles of the South Branch.

“We jumped in with old tennis shoes and a pair of shorts and just walked in the water,” Slifka recalled, adding that wading was easier than pushing through trees and brush on the bank. “You could see where the springs came in. Some you couldn’t see, but you could feel it.”

The headwaters walk, which they hope to repeat in 2025, is just one part of a complex planning process for the Turkey River Headwaters and Chihak Creek Watershed Project that Slifka coordinates. Around the state, watershed projects tie the goals of farmers and landowners to the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy.

Shaffer, a local farmer who has worked for the Howard SWCD since 2001, started a plan for the county’s Silver Creek watershed in 2014. He’s the coordinator for that watershed, which flows into the Upper Iowa River, and he often collaborates with Slifka.

Every summer, the duo teams up to check on water quality at eight temperature gauges along the Turkey River headwaters. They measure levels of nutrients with test strips and send bottles of water to Coe College in Cedar Rapids for lab analysis.

It takes more than a lab test or river walk to really understand an entire watershed. We climb back into Slifka’s truck and head a few miles east, stopping at several new wetlands and a strip of newly planted native prairie emerging at the edge of a cornfield.

Then, we pass section after section of farm fields protected by cereal rye cover crops. In some fields, the rye is still green and in other fields it has already been sprayed to stop its growth. At one, a pheasant walks from a ditch into a field, its colorful head bobbing above golden-brown terminated rye.

When Slifka first waded the shallower stretches of Turkey River nearly 10 years ago, less than 2% of his 62,000-acre watershed was protected by cover crops. Today, it’s well over a quarter of the watershed, a change Slifka described as “kind of a movement” locally. That sense was confirmed at a nearby farm, where sprayer passed quickly over a field of rye.

“We’re just finishing spraying,” the farmer, Brandon Reis, said after he pulled up to us in his pickup. “In this area, cover crops are getting to be kind of expected.”

Reis was using no-till when he started farming in 2012, and he has been planting his entire farm with cover crops for the past five years. Along with farming, Reis sells rye to neighbors and helps coordinate aerial seeding by Midwest Aviation. He is also the treasurer and a past president of the county’s Farm Bureau.

“Once a certain amount of people start doing it, then other guys see they’re making it work, so it must not be that bad,” Reis said, adding that his family first tested cover crops in 2013 to protect soil left nearly bare after a wet spring prevented planting.

The farm has fields in both the Silver Creek and Turkey River watersheds of Howard County, a region where the slightly rolling Iowan Surface landform transitions to Northeast Iowa’s unglaciated, rugged Driftless Area rich with porous limestone bedrock sitting close to the surface.

“There’s a lot of farms that just don’t have that much topsoil,” Reis says. “With cover crops, we were chasing erosion control…we didn’t understand then the benefits to biology.”

No-till helps restore soil health with obvious signs, like earthworms. Cover crops have also ramped up the earthworm population. Reis recently turned up a shovelful of soil with 11 worms, which he estimated amounts to 1.5 million per acre.

Better soil health aids farming in many ways, reducing soil compaction and making it easier to get into fields earlier in the spring. Today, the soil “is like a firm sponge,” Reis said.

He said farmers know there is risk to starting cover crops as well, including the possibility of losing yields if the practice is introduced the wrong way.

That’s where Slifka comes in. By using several state and federal cost-share programs, he can offer farmers as much as $65 to $85 per acre to try out cover crops. Farmers are also helping each other navigate the fine points of this conservation practice.

Reis said there are a lot of supportive Facebook groups for farmers curious about cover crops, such as Everything Cover Crops and North Iowa Cover Cropping.

Slifka credits Shaffer with giving cover crops and conservation practices an early boost in a county with a proud history of conservation. Shaffer was first hired to promote grass buffers beside streams, now a common sight along with grass waterways. All these practices add up to improved water quality, one sign of which is the return of native trout populations to some streams in the county.

More improvements are coming. Howard County and others in the area will soon be using the “Batch and Build” approach to help farmers line up financial support and contractors for bioreactors and saturated buffers. These two edge-of-field practices, like cover crops, lower nitrates entering streams.

Howard County has much to be proud of, including several well-known college wrestlers. One of them was Norman Borlaug, and he’s even better known as the scientist who in 1970 won the Nobel Peace Prize for developing high-yielding wheat. His discovery led to a global green revolution that saved millions of people from starvation.

Slifka, a fellow college wrestler, serves on the Iowa Wrestling Hall of Fame board, as did his father, Steve. Slifka’s father-in-law, Chad Bordwell, is helping restore Borlaug’s birthplace farm at the southern edge of the county.

Just as Borlaug’s drive and dedication led to one revolution in agriculture, the hard work of Slifka, Shaffer and others in Howard County may lead to another – farming which treads softly on the land and streams.

Published June 28, 2023