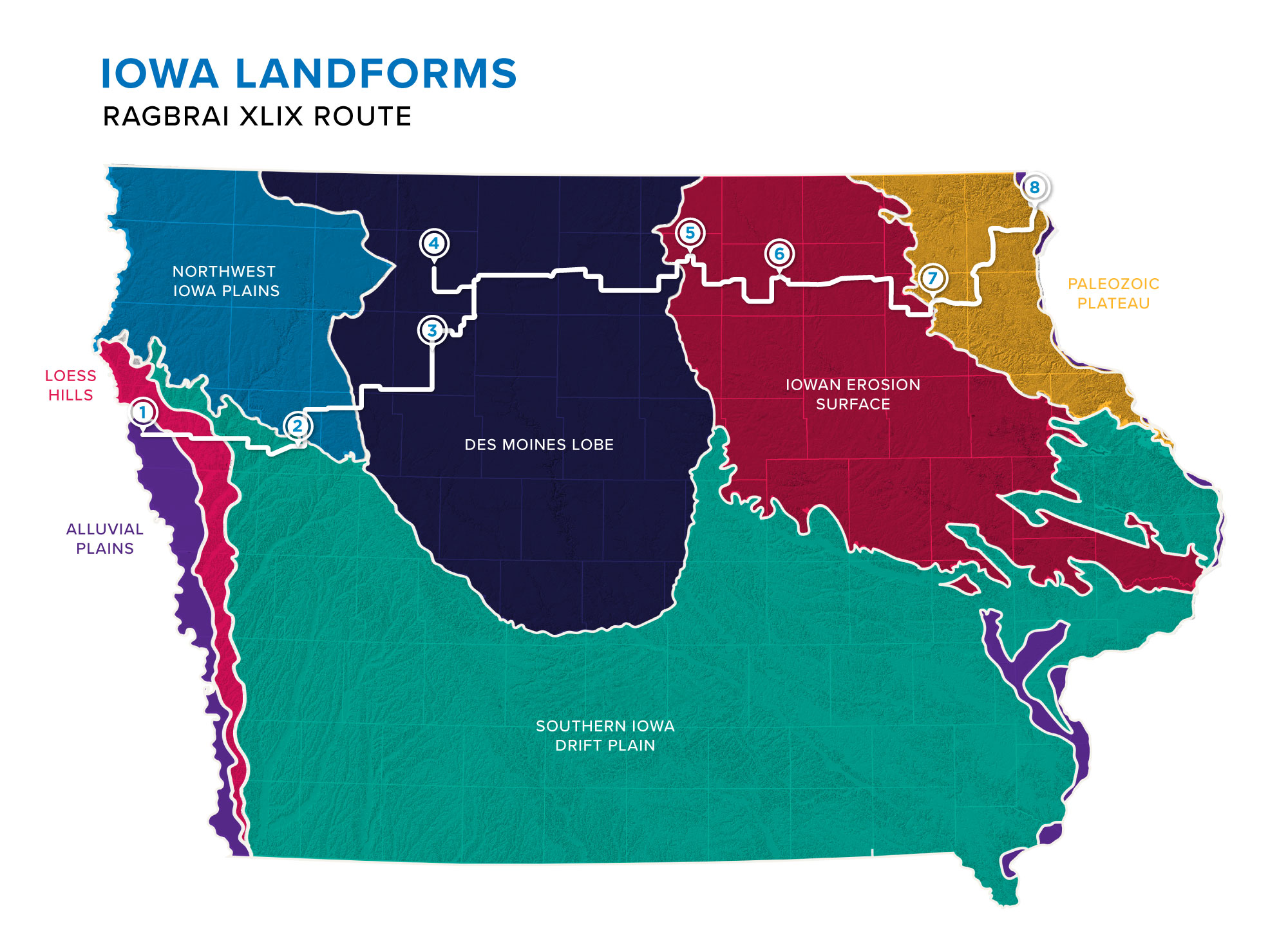

RAGBRAI riders will bike through six out of seven landform regions in Iowa, many created by glaciers more than 13,000 yeras ago. They not only created a challenge for cyclists, but also for conservation due to unique soils and landscapes. Dan Looker, IAWA writer and RAGBRAI enthusiast, describes the route’s unique geography riders will see.

By Dan Looker

On Sunday, July 24, more than 16,000 bicycle riders will pour out of Sergeant Bluff in northwest Iowa. It’s day one of seven on the Register’s Annual Great Bicycle Ride Across Iowa, or RAGBRAI. Novices will glide eight miles east across the Missouri River flood plain to a revelation: Iowa is not flat.

The rolling hills and beautiful landscapes that make the ride so enjoyable (and often tough), were carved out years ago by the glaciers of Iowa’s past. They created 7 major landform regions in Iowa; six of them are part of the route. Here’s what to expect in a few.

Loess Hills

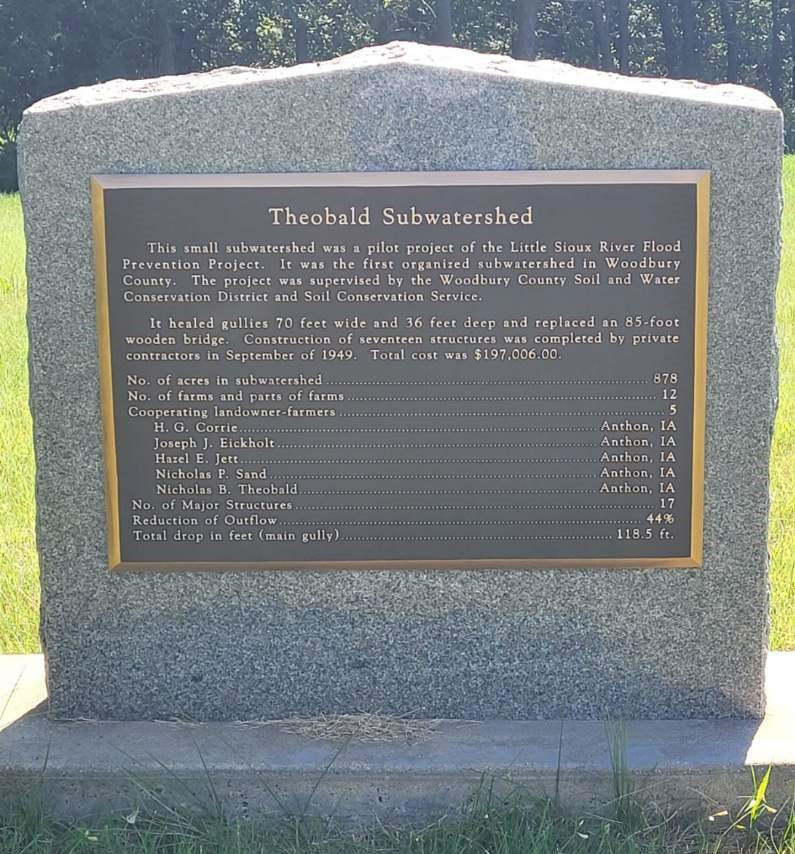

The Theobald Subwatershed was a pilot project of the Little Sioux River Flood Prevention Project. It is comprised of 878 acres and 12 farms.

Bikers will gear down at the Loess Hills, a range of rugged wind-blown silt stretching along Iowa’s western border.

The silt is a product of glaciers pulverizing rock into fine powder over ten thousand years ago. The fine grains of silt blew in the wind until they collected in the Missouri River Valley to form dunes, then ever-larger hills until they became the second largest loess formation in the world, second only to the Loess Plateau near the Yellow River in China.

“The Loess Hills are very fertile and good for growing crops,” says Randi Prichard, a soil conservationist in USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) office in Sergeant Bluff. “It’s the same soil up to 90 feet down, but as hilly as it is and as fine as the soil particles are, a lot of it is extremely erosive.”

Woodbury County, where Prichard works, has some of Iowa’s oldest fixes against erosion. Near Anthon, a stone marker commemorates the Theobald Subwatershed project—small dams and larger structures finished in 1949. Today, the county has approximately 400 dams and a full-time staffer to maintain them.

Without the larger dams above them, “you could flood out a town pretty easily,” Prichard says. The farmers’ terraces and grassed waterways are also essential in keeping the soil on the farm during large rain events.

Past the stone monument, an NRCS sign marks a filter strip on the farm of Keith and Dorothy Kuhn. Filter strips are sections of grass that trap sediment and nutrients leaving fields.

Des Moines Lobe

On Monday, the ride smooths near Pocahontas, entering the biggest feature of northern Iowa’s landscape–the sweep of the Des Moines Lobe of the Wisconsinan ice sheet. That last glacier bulldozed as far south as Des Moines. By 11,000 years ago it was melting back into Minnesota, leaving rich minerals behind, pocked with lakes and marshes. Forests followed, then prairies. For 10,000 years, the minerals and decaying roots of tall grasses created some of the world’s most fertile farmland – what many of us know as Iowa’s black gold.

Water quality is a large challenge in the Des Moines lobe. Underground tiles in this poorly drained farmland carry nutrients (both native to soils and man-made) into streams. Phosphates and nitrate reduce water quality, even to the Gulf of Mexico. Farmers, aided by NRCS, and state and local programs are starting to clean water with new technology. Bioreactors and saturated buffers at field edges remove nitrate in tile water. More commonly, farmers here are quitting tillage or tilling in strips. They’re planting cover crops like rye to scavenge nitrates.

Unfortunately, cover crops and no-till aren’t visible in summer fields. Nor will RAGBRAI riders see bioreactors or saturated buffers, staff at all 14 county NRCS offices along RAGBRAI tell me. These can be hard to see since they do their jobs underground.

Iowan Surface

On Wednesday evening, bikers will arrive in the Iowan Surface which features long rolling slopes and expansive views.

During this leg of the route, they’ll see a restored wetland near Charles City in Floyd County, funded through the USDA Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP).

Wetlands are often restored in parts of fields that don’t produce high yields because they collect so much water. Wetlands are shallow pools that filter water before it travels downstream. They also have wildlife benefits, attracting local and migratory birds.

“It does a good job,” says Joshua Heims, the county’s NRCS district conservationist. “If the rainfall is slow, it’s pretty close to 100% nitrate removal.”

On Thursday, Heims will be at one of five conservation information tent stops pitched each day for riders. They offer free bananas and postcards of conservation practices, something NRCS and other conservation groups have done since 2003.

The Driftless Region (Paleozoic Plateau)

On Saturday, the final day, riders leave West Union in Fayette County to enter a landscape missed by glaciers–the Driftless Region. Its ancient limestone bluffs are steep but stunning. It will also challenge bikers with a nearly 3,000 foot climb.

“From a water quality standpoint, it’s incredibly sensitive here,” explains LuAnn Rolling, NRCS district conservationist for nearby Allamakee County, where the ride ends.

The county has 2,000 limestone sinkholes where water flows from fields directly to groundwater. So farmers leave circles of trees or vegetation around the sinkholes. They plant strip crops—rows of corn or soybeans between strips of hay or small grains. They’ve long used no-till and cover crops. All of this protects the county’s 16 cold water trout streams.

Back in Fayette County, volunteers have posted 6 signs about conservation practices. Any hard pedaling past them will be worth it, says Aaron Anderson, Fayette County NRCS district conservationist. Riders will see wetlands, tree plantings, prairie remnants, and pollinator plantings.

“You are in for a real treat riding through Northeast Iowa!” Anderson says. Provided you don’t mind the hills!

Most of the 2022 RAGBRAI route is in the project geography of the Iowa Systems Approach to Conservation Drainage. This is a conservation project co-led by IAWA and the Iowa Department of Ag and Land Stewardship that helps farmers pay and plan for conservation drainage. Learn more here.